Have you got what it takes to lead in uncertain and volatile times?

On a recent visit to Germany, imagine my delight when discovering that my parents’ dusty slide projector was still fully functioning! (For the millennials of my readers: Slide projectors are a throwback into the ancient analogue world of camera film). All of a sudden, there were hundreds of family slides to choose from. One evening, we selected a great sample of holiday slides. Watching these pictures come alive on a big screen in a darkened room took me right back to those memorable mountain climbs of my childhood. Growing up close to the Alps, my parents introduced my brother and me to mountain hikes from an early age. Yet, with the knowledge of hindsight, I realised that most of those great mountain climbs wouldn’t have been possible, had it not been for our mountain guide, Hermann, who we engaged as our mountain leader for several years.

Leadership strengths

When I recently came across a review of a new leadership book by Christopher Maxwell, Lead Like a Guide: How World-Class Mountain Guides Inspire Us to Be Better Leaders, I was immediately intrigued to find out what he had to say about the leadership differentiators of mountain guides. In interviews with many different mountain leaders, he found that there were six different key leadership strengths that they all had in common. They were:

Let me take you on a mountain climb to the Zuckerhütl, a mountain in Tyrol, Austria, to demonstrate these leadership strengths in Hermann, our guide. At 3,505 metres (11,499 feet), the Zuckerhütl is the highest peak of the Stubai Alps. It derives its name, the German for sugarloaf, from its conical shape although nowadays it doesn’t do its name justice any longer as the last 80 metres to the summit are rock only.

Social intelligence

Our family of four and our friends, another family with two kids, planned to climb this mountain one summer. Hermann had guided my family before but wasn’t yet very familiar with our friends. With his social intelligence, he very quickly established positive relationships with all tour members, ranging from tweens (some of them scared and lacking self-assurance) to mums and dads in their early forties (with different physical abilities and resilience levels). I now realise that Hermann had developed an amazing sense of what peoples’ skills and talents were after working with them for just a few hours. He helped each of us to find our role in the process, helping us work together as a team.

From my own experience in the coaching and consulting world, I know how important it is to be able to interact comfortably with people in any type of organisation, no matter their function, rank, or location. The skill to quickly establish positive relationships is as crucial in the mountains as it is in highly competitive industries and markets.

Empowerment

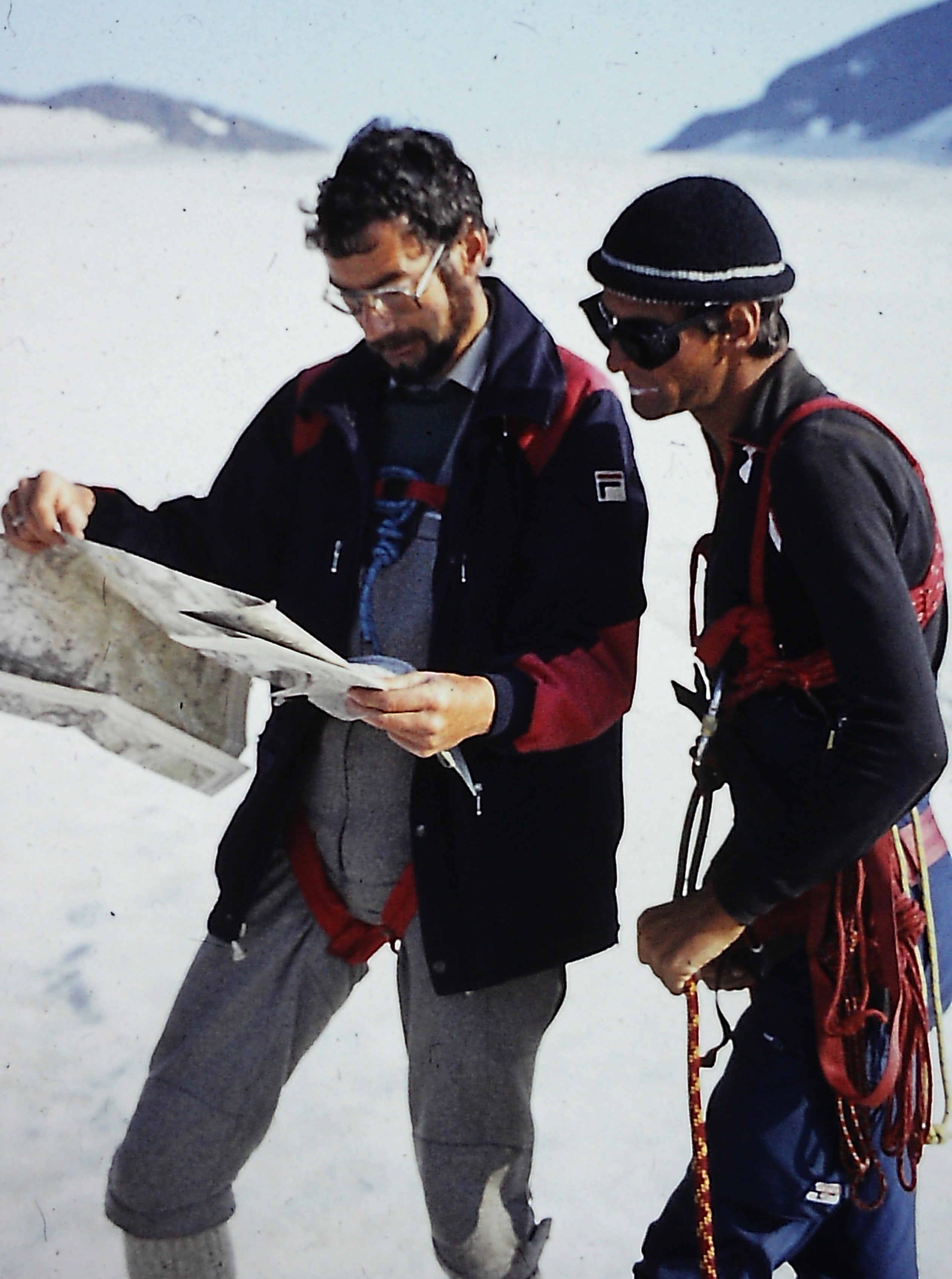

Empowerment is wonderfully displayed in this photograph.

Notice how it is my dad on the left who is holding and studying the map. In fact, he is a real expert at reading maps, and Hermann was fully aware of this skill and enabled my dad to develop it much further than he ever thought possible himself. Observe also how Hermann is standing next to my dad, slightly back, ready to offer support and guidance, but only if necessary.

In a recent report, internationally-certified mountain guide Christian Santelices says: ‘You really are building others up, inspiring clients to find in themselves what they might not have thought themselves capable of.’

Risk awareness

Mountain climbing involves lots of risks: the mountains with their multitude of terrains such as glaciers, ridges, debris, rock and ice surfaces; the weather with its unpredictable patterns at high altitude and the mountain climbers with the entirety of human traits including fallibilities such as over-ambition and hubris.

Mountain leaders therefore need to be risk aware. Early in the day of the ascent of the Zuckerhütl, we had to traverse a big glacier. That year there was still plenty of snow cover over the crevasses which criss-crossed the glacier in their hundreds. However, in some places that cover wasn’t very thick. Hermann had to weigh up the risk of traversing the glacier (reducing the time it would take to cover this part of the climb in comparison to circumventing it) with the danger of falling into a crevasse, something we had all been trained on but an event you’d want to avoid as much as possible. With such a large team to lead, Hermann decided to traverse rather than circumvent, but he minimised the risk by pushing his ice-pick deep into the ground before every step he took, checking for sudden lack of resistance which would have predicted a crevasse underneath. We made it across without anybody having to use their Prusik ropes (which only come into action if you fall into a crevasse)!

Adapting to changing conditions

After several hours of climbing, just before the last stretch of the ascent to the Zuckerhütl (where the main picture was taken) the mums suddenly decided to stay behind and let the rest of the party ascend. For Hermann, this meant having to adapt to new circumstances quickly: everybody else had to walk in a different order on the rope for this final stretch of the climb.

The optimum order of people on the rope is dependent on the mindset and physical ability of the climbers as well as the terrain and direction of travel. Hermann also had to make a quick choice on whether to take a break or not – were the clouds coming in more quickly than predicted? Would the snow bridges on the later descent still be strong enough in the afternoon hours? How many other teams were ascending and descending and what did that mean for our team’s safety?

Building trust

Looking back, I am amazed at how Hermann instilled a strong foundation of trust in each team member. He facilitated this trust-building process from the very beginning, creating a positive learning environment by modelling behaviour and providing support. He would help us to break down challenges into really small steps, making them much more achievable and building up trust at every stage.

As a team member in Hermann’s team, you knew that you could totally lay your trust in him, the team and therefore yourself, whether you were traversing a gaping crevasse, manoeuvring a tricky rocky ledge or trusting the strength of the rope on a vertical descent. Often, we found ourselves looking back at our routes from the summit or the mountain hut at the end of the day and wondering how we’d managed it all, and for me, it simply comes down to this leadership skill – building trust!

To put this into the business context, John Sims, Managing Director & CFO at Snowden Lane Partners, aptly says in the report quoted above; “Without trust in your teammates, you will only do as much as your faith in your own limited abilities will take you. You will not risk stretching your own expertise or experience, and you are unlikely to learn as much from those around you. Each person will revert to being an island, placing trust only in their own abilities and therefore limiting individual and corporate horizons.”

Big picture thinking

The lure of the summit is strong. The lure of the Zuckerhütl was strong! And you will be glad to hear, that most of us (except the mums who enjoyed their sun bath) made it up to the top! Guides know that their clients want to reach the summit of the mountain, but they also know that they need to come down again safely.

The next day of a mountain tour might involve another climb which will require more physical and mental strength or it might be a rest day. All of that needs to be taken into account. Looking back on our adventures many years ago, I recognise and appreciate that Hermann always had this bigger picture in mind. He deployed strategic thinking at every single step of the way, which in my view, made him not only a mountain leader, but a world-class mountain leader!

Katrin Homer